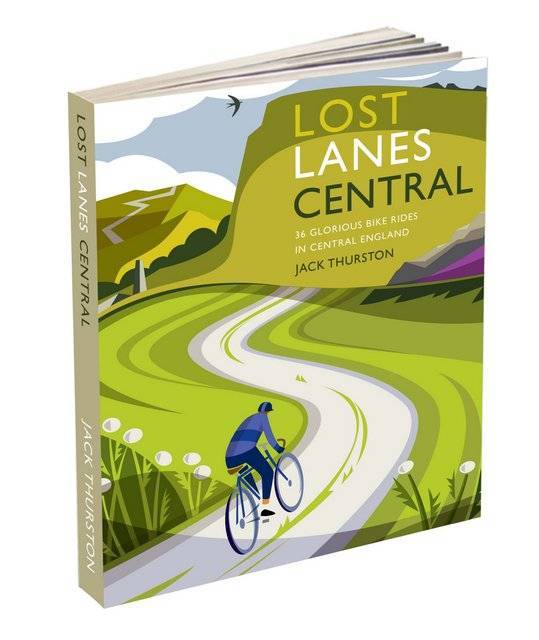

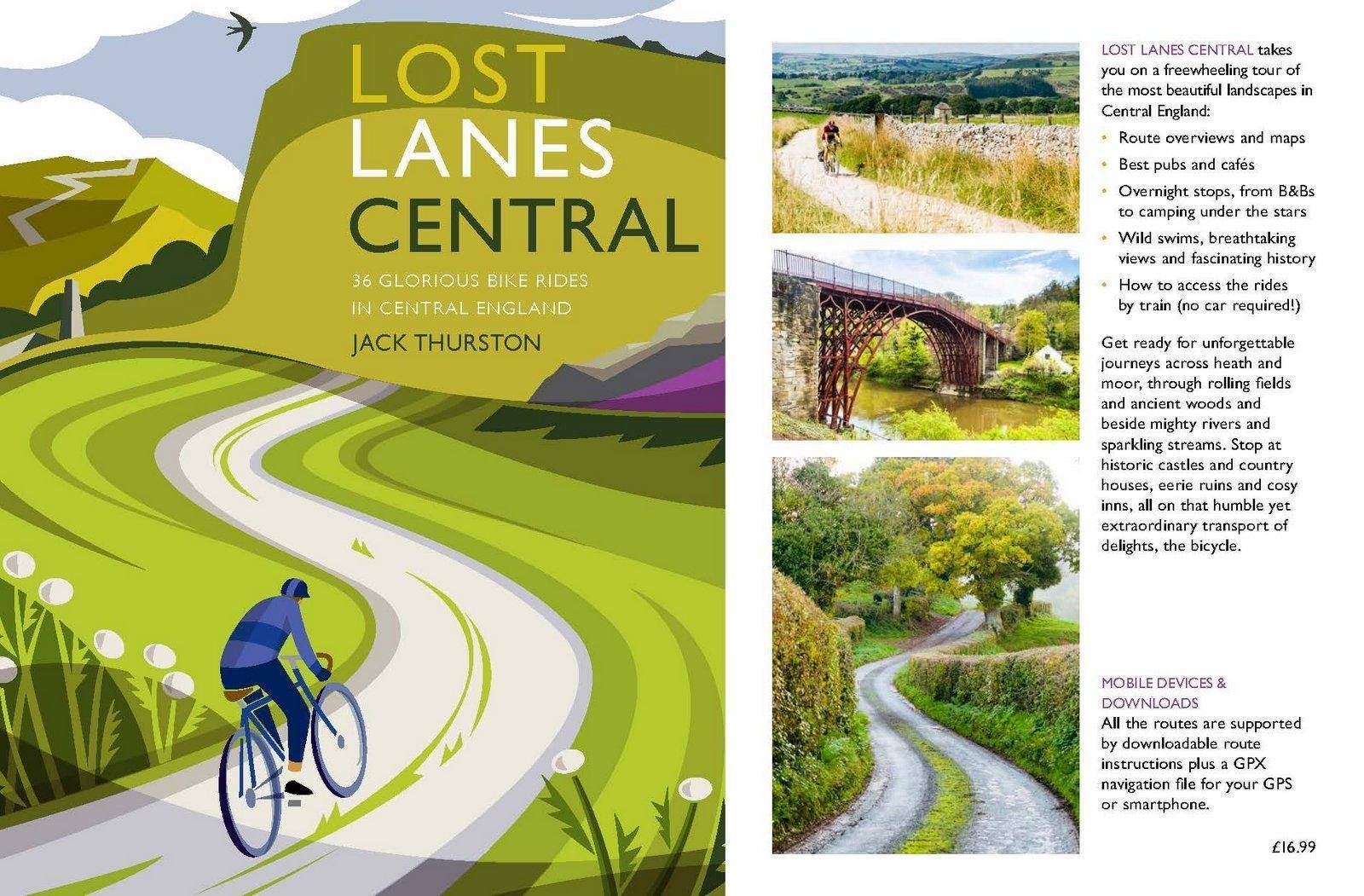

Jack Thurston, best-selling author of the Lost Lanes series takes you on a freewheeling tour of the hidden lanes and forgotten byways of the Midlands and beyond, from the windswept hills of Shropshire to the big skies of Lincolnshire, from the crags of the Peak District to the comely villages of the Cotswolds.

- Enjoy the traffic-free trails of the Peak District – dramatic landscapes, grand country houses and industrial archaeology

- Explore the Cotswolds on its quietest country lanes and hidden byways, stopping at cosy pubs and breathtaking sunset viewpoints

- Follow in the tyre tracks of Edward Elgar to the summit of the Malvern Hills for some of the most splendid views of England

- Discover secret Birmingham on its vast network of canal towpaths and traffic-free urban greenways

- Graded from easy to challenging, with listings of the best pubs and tea stops, wild swim spots, viewpoints and accommodation too. Accompanied by a dedicated website, downloadable

- GPX files, turn-by-turn route instructions and detailed maps. All rides are accessible by train.

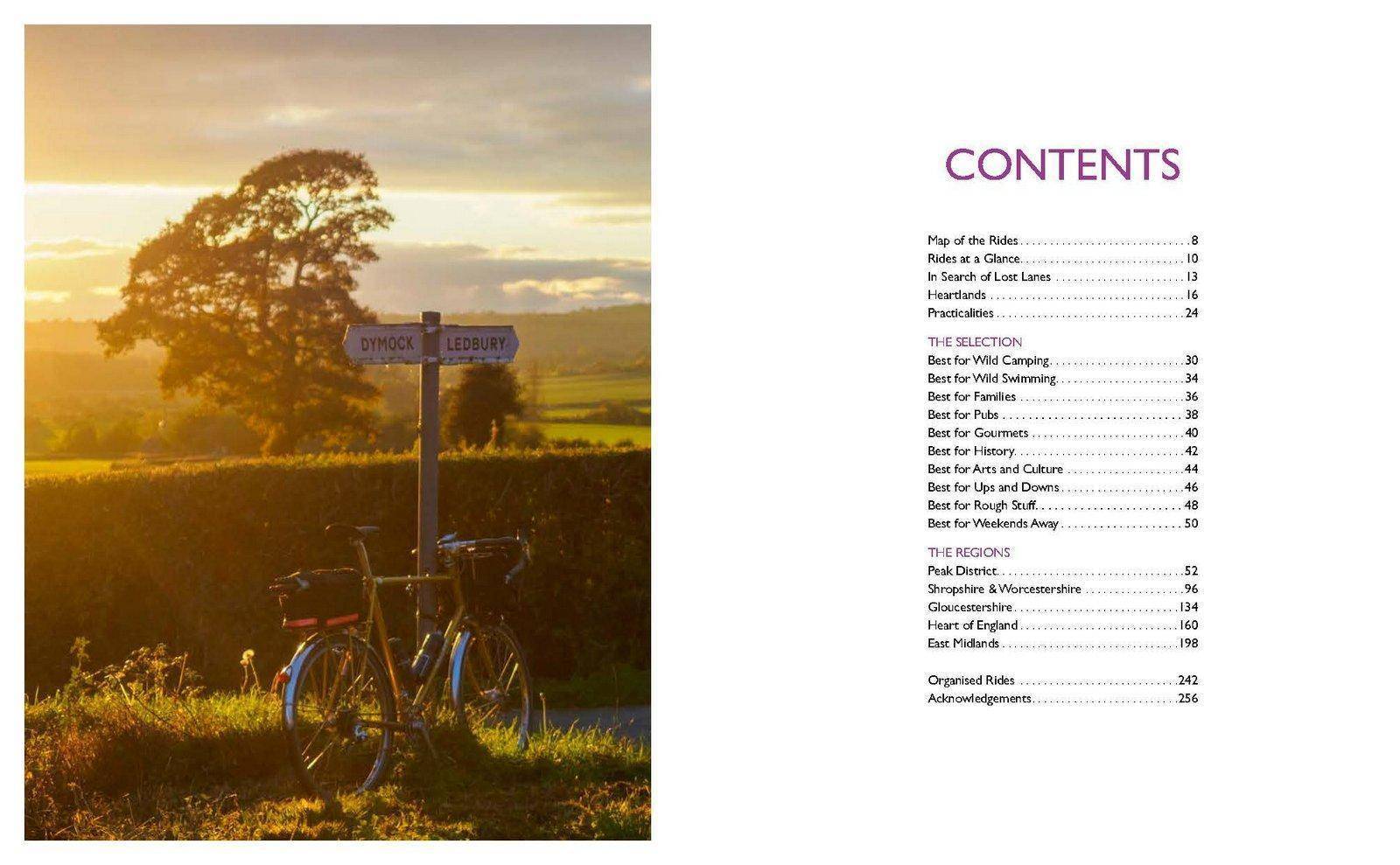

Table of Contents

Map of the Rides 8

Rides at a Glance 10

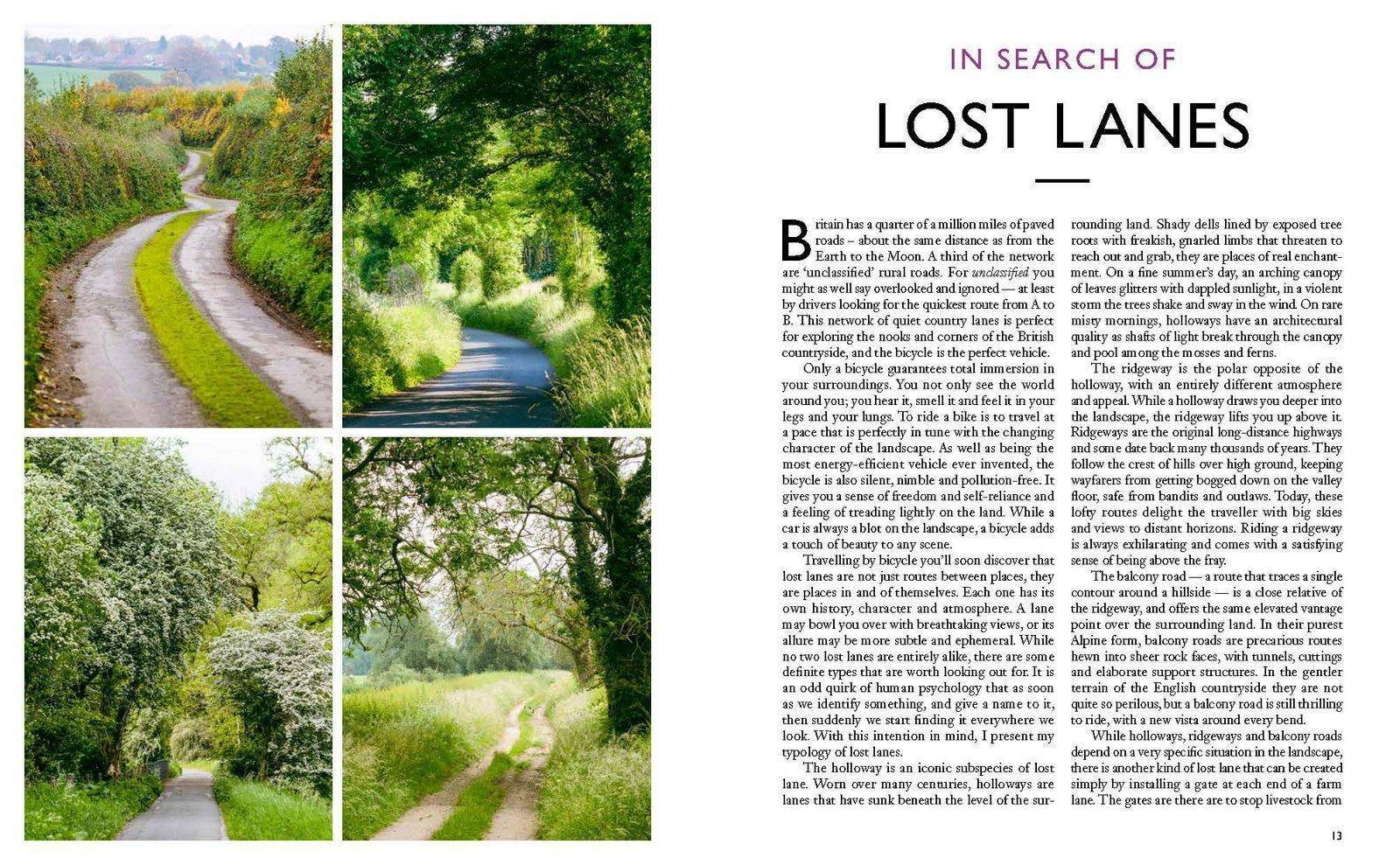

In Search of Lost Lanes 13

Heartlands 16

Practicalities 24

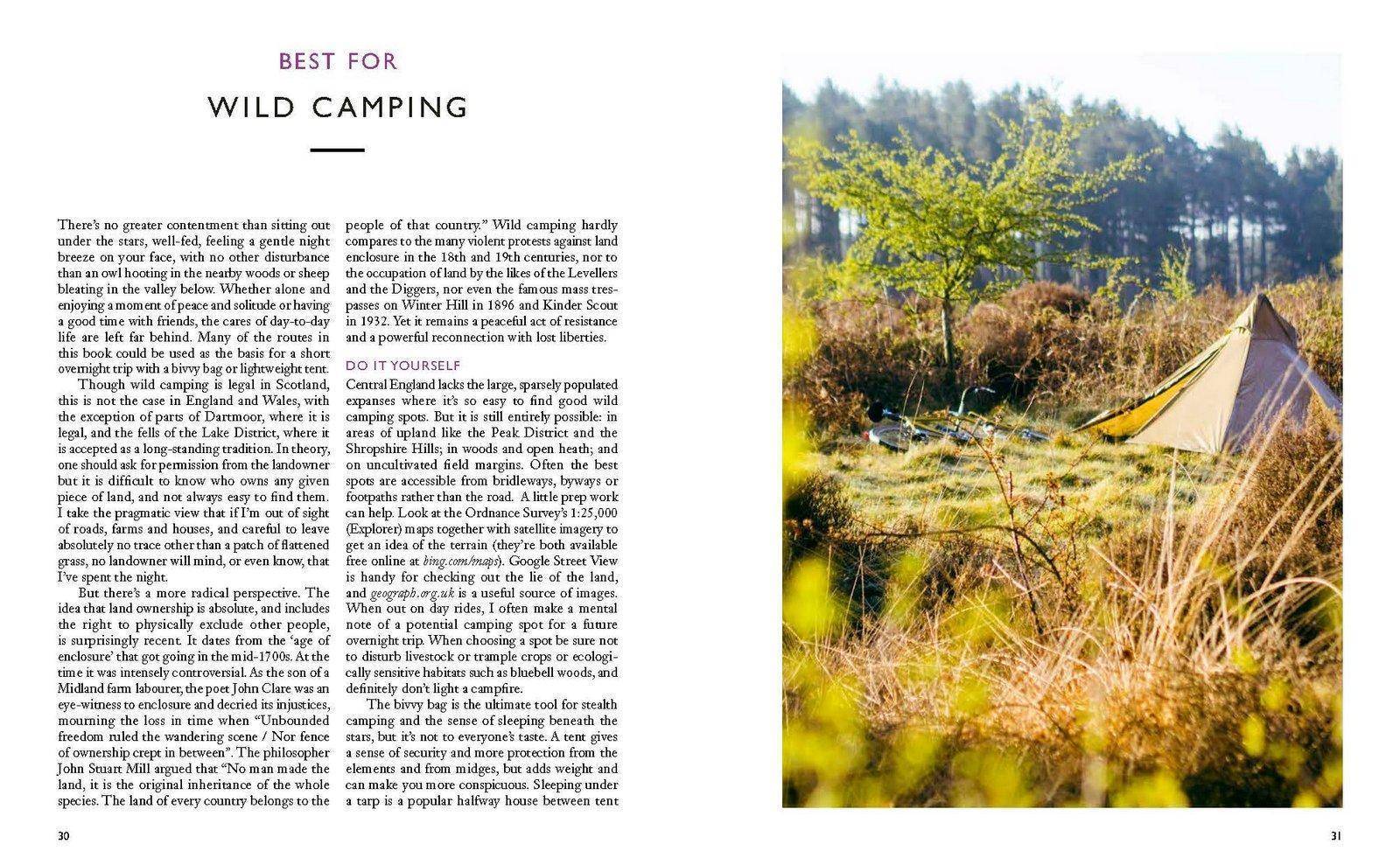

Best for Wild Camping 30

Best for Wild Swimming 34

Best for Families 36

Best for Pubs 38

Best for Gourmets 40

Best for History 42

Best for Arts and Culture 44

Best for Ups and Downs 46

Best for Rough Stuff 48

Best for Weekends Away 50

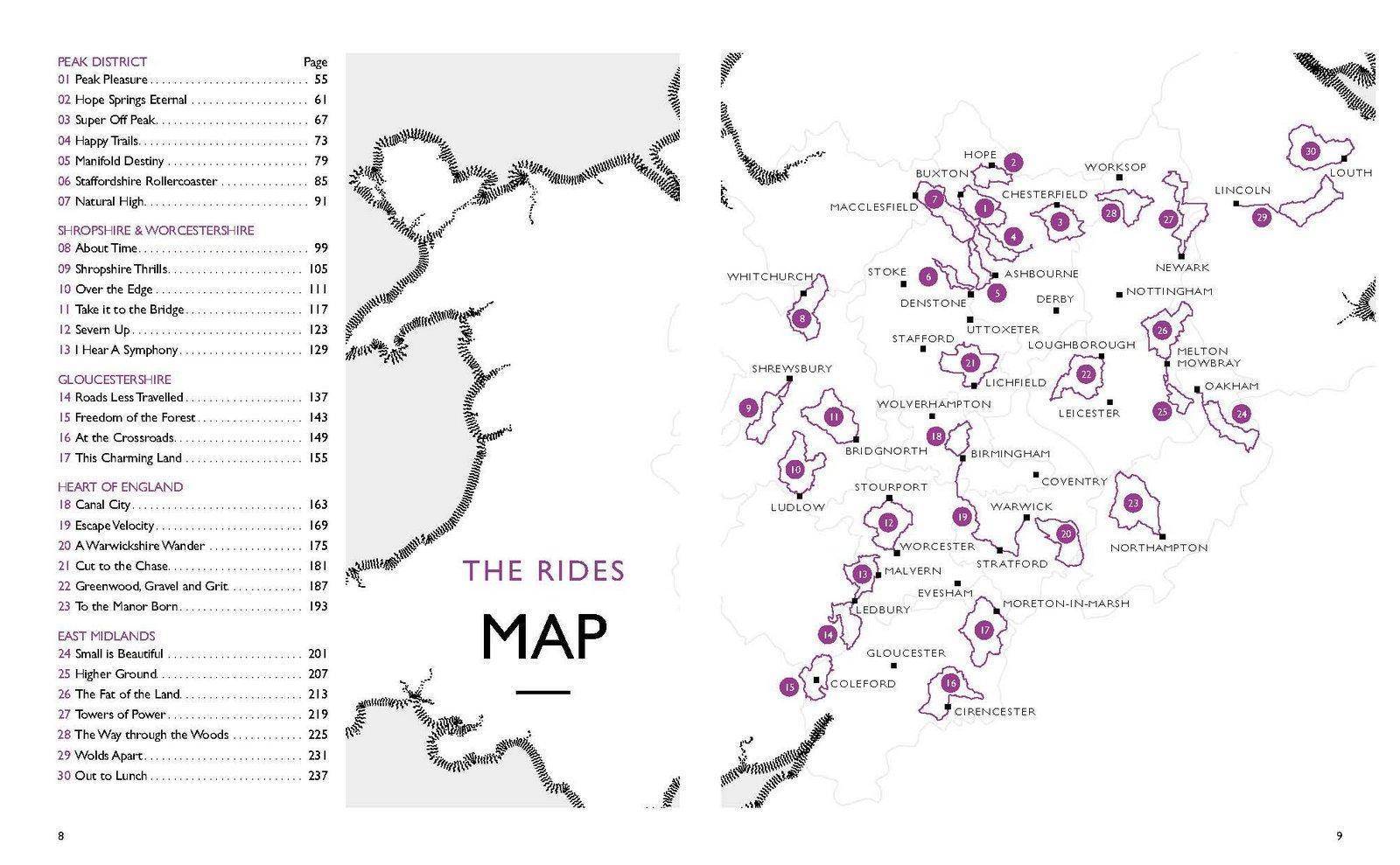

Peak District

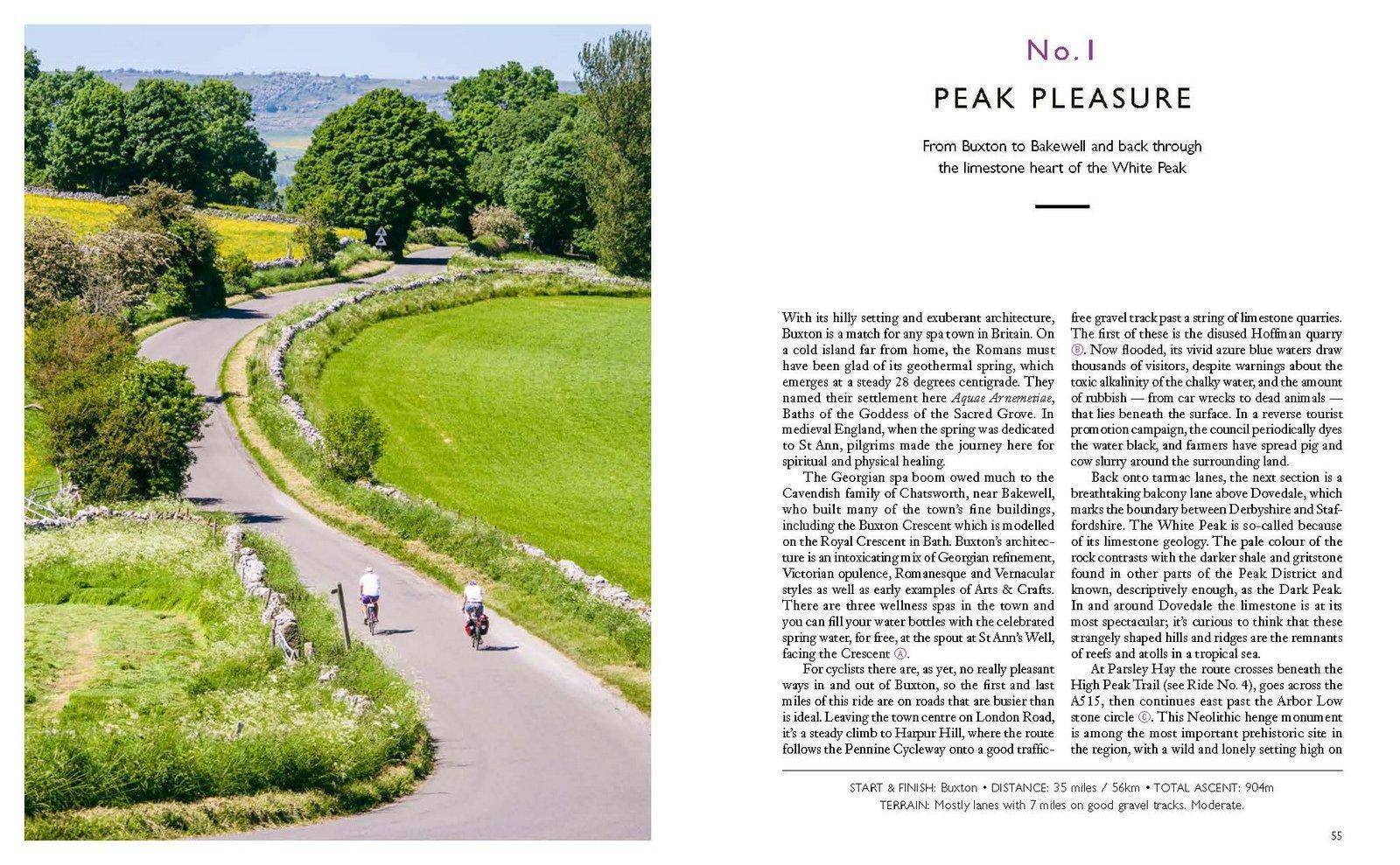

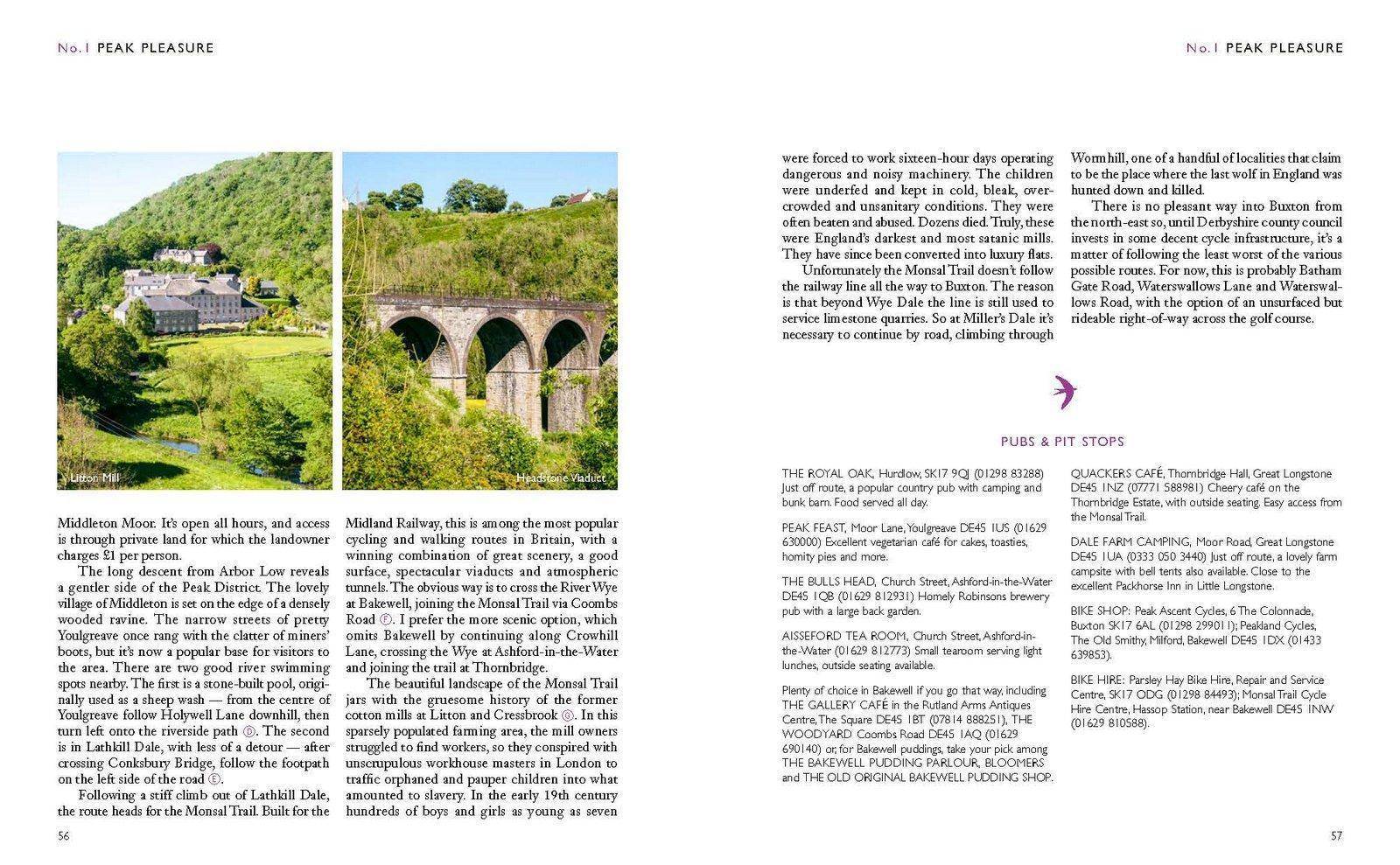

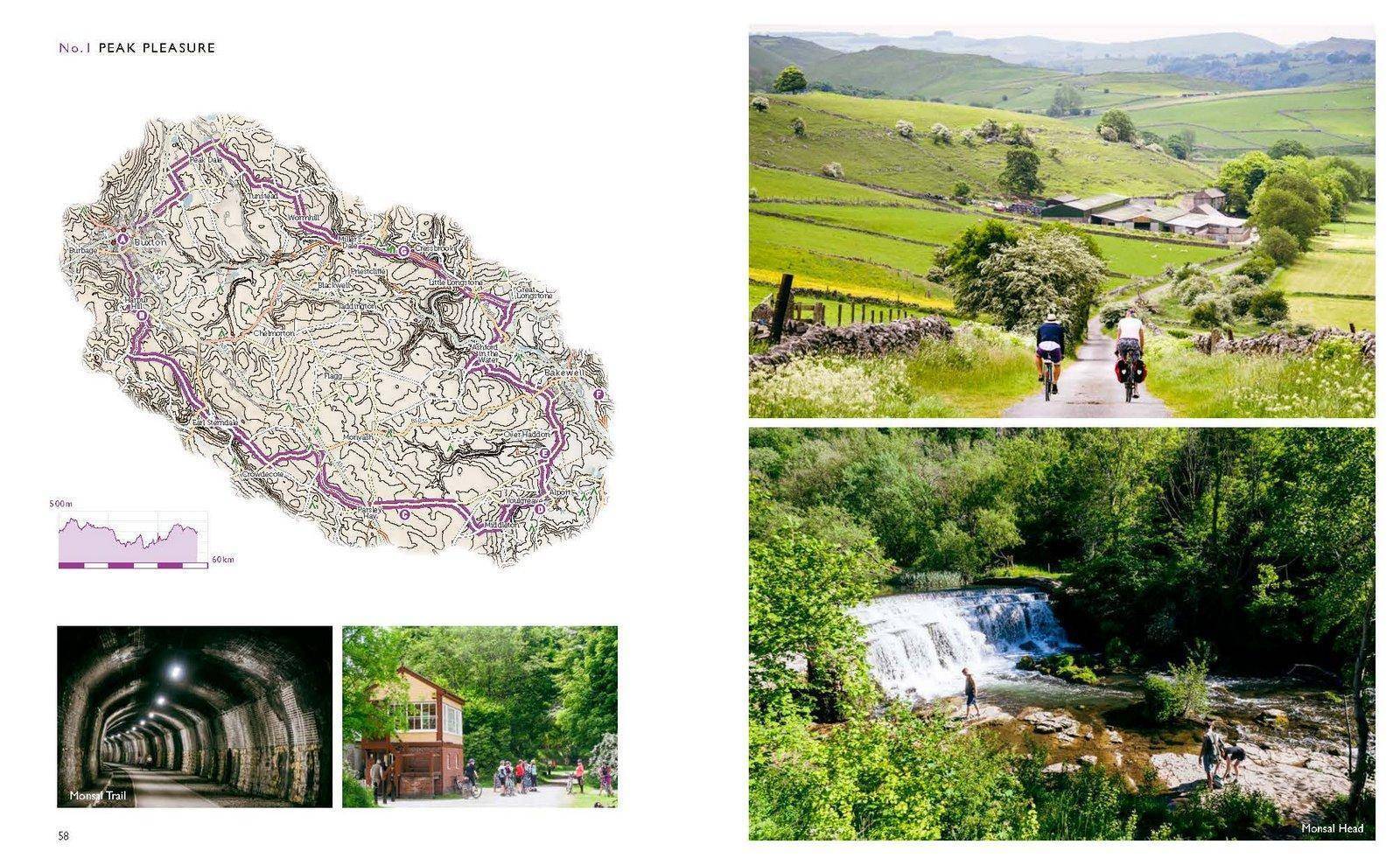

01 Peak Pleasure 55

02 Hope Springs Eternal 61

03 Super Off Peak 67

04 Happy Trails 73

05 Manifold Destiny 79

06 Staffordshire Rollercoaster 85

07 Natural High 91

Shropshire & Worcestershire

08 About Time 99

09 Shropshire Thrills 105

10 Over the Edge 111

11 Take it to the Bridge 117

12 Severn Up 123

13 I Hear A Symphony 129

Gloucestershire

14 Roads Less Travelled 137

15 Freedom of the Forest 143

16 At the Crossroads 149

17 This Charming Land 155

Heart of England

18 Canal City 163

19 Escape Velocity 169

20 A Warwickshire Wander 175

21 Cut to the Chase 181

22 Greenwood, Gravel and Grit 187

23 To the Manor Born 193

East Midlands

24 Small is Beautiful 201

25 Higher Ground 207

26 The Fat of the Land 213

27 Towers of Power 219

28 The Way through the Woods 225

29 Wolds Apart 231

30 Out to Lunch 237

Organised Rides – 6 of the best

About the author

Jack has spent most of his life exploring the British countryside by bike. As presenter of The Bike Show on Resonance FM, he has brought his affable, infectious velophilia to London’s airwaves, attracting an enthusiastic worldwide audience via the popular podcast edition. He has featured in a series of hour-long documentaries on slow travel aired on GCN+, part of the Global Cycling Network.

Introduction

In sketching this portrait of Central England I have deliberately chosen a large canvas. As well as including the traditional core of the Midlands, it covers an area from the Cotswolds to the Peak District, and from Lincolnshire to the Welsh border. I am aware that this takes in a few places that some consider to be Northern, and an entire county that the Government views as part of the South-West. As justification for drawing the lines where I have, I invoke no less powerful an authority than the once-mighty Kingdom of Mercia. For three centuries Mercia was the richest and most successful of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that emerged between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Norman Conquest. Though more than a thousand years ago, their names still echo in the mental geography of this island: Northumbria, East Anglia, Wessex, Essex, Kent and Sussex. Scotland to the north, Wales to the west, and right there in the middle, Mercia.

Paradoxically, the name Mercia is derived from the Old English Merce, and means ‘people of the borders’. The borders in question were with the Celtic Britons the Mercians had driven to the west (beyond King Offa’s famous dyke), and with the Kingdom of Northumbria (i.e. ‘north of the Humber’). The River Thames formed Mercia’s southern border with Wessex. Following the shock of the Viking invasion, a long fightback led by King Alfred of Wessex saw Mercia regain its lost lands and the unification of all the Anglo-Saxons into a new kingdom of England. The land of the Mercians has been in the thick of the action ever since, witnessing the dynastic struggles of the Wars of the Roses, the religious upheavals of the Reformation and the decisive battles of the Civil War. But the region’s greatest era — a time of truly global significance — was when it became the fiery crucible of Britain’s industrial revolution.

An Explosion of Ingenuity

Accidents of nature provided the raw materials for its earliest industries, from the salt springs of Droitwich to the veins of lead in hills of the Peak District, the iron, coal and lime in the rock strata at Coalbrookdale, the fast-flowing streams that powered the earliest cotton mills and the mineral-rich waters of Burton-on-Trent that are perfect for brewing pale ale. But natural resources would have been nothing without a less tangible ingredient, the spark of invention. The cascade of innovative new ideas in science, engineering, economics and political thought produced by the people of the Midlands of the 1700s is down to the unusually close and creative relationships between the region’s leading scientists, philosophers and entrepreneurs.

The key nexus of the so-called Midlands Enlightenment was the Lunar Society, a Birmingham dinner club and informal learned society that met during the full moon, when the extra light made the journey home easier and safer. Among its most colourful members was Erasmus Darwin, who sometimes hosted meetings of the society at his house in nearby Lichfield. A philosopher, a poet and a medical doctor, Darwin was also a natural scientist and an inventor. He was the first person to give a full description of how clouds form and of photosynthesis in plants, and drew up designs for a speaking machine, a copying machine and a ‘flying chariot’ or aeroplane. But Lichfield’s answer to Leonardo da Vinci ran into hot water with his early theory of human evolution that flatly contradicted the teachings of the Bible. Branded a crank by the establishment, it fell to his grandson Charles (born and raised not far away in Shrewsbury) to prove that Erasmus had been onto something after all.

Among the other ‘Lunarticks’, as the group cheerfully referred to themselves, were James Watt and Matthew Boulton in Birmingham. They not only perfected the steam engine but also pioneered the concept of mass-producing goods in a large, specialised ‘manufactory’. Along with Josiah Wedgwood’s world-beating pottery works in Staffordshire, and Richard Arkwright’s cotton mills in the Derwent Valley, Central England led the world into the modern era of mass production and the consumer society.

It wasn’t all about successful entrepreneurs and wealthy amateur scientists with laboratories in their country estates and elegant townhouses. The explosion of ingenuity was underpinned by inventive people of more modest means. Britain was an island of tinkerers and fettlers, nowhere more than in the Midlands. Its skilled craftspeople were creative, hard-working, self-reliant and independent-minded. Many were religious nonconformists such as Quakers whose founder, George Fox, came from Leicestershire. Their dissenting religion meant they were barred from elite universities and from jobs in the government and the military. Free from the restrictive hierarchies of feudalism, courtly life, and the church, the prevailing culture was one of free-thinking and social mobility. They trusted one another and were willing to pool resources and share ideas. Abraham Darby’s pioneering ironworks in Coalbrookdale owed much to the region’s Quaker network. Birmingham Quaker John Cadbury founded a chocolate empire that sought to forge a more humane form of capitalism. The Bournville district of Birmingham was conceived by the Cadbury family as ‘a factory in a garden’ where employees were provided with good quality homes, amenities for leisure and learning and plenty of green space. It was a radical new idea that helped inspire the garden city movement. The Cadbury family also campaigned against child labour, poverty, animal cruelty and alcoholism, and founded new schools, colleges and hospitals. In the 1920s and 1930s they supported Quaker aid for European war refugees, and played a major role in setting up the Youth Hostel Association.

While John Cadbury was expanding his chocolate business, over in Leicestershire, a itinerant Baptist preacher, pamphleteer and furniture-maker named Thomas Cook had a simple idea that led to another new and successful business empire. In 1841 Cook chartered a passenger train on the recently opened railway line to take some 500 fellow temperance campaigners on a day trip from Leicester to attend a teetotal rally in nearby Loughborough. For a shilling, Cook’s passengers got round trip train travel, band entertainment and refreshments. The excursion was a success and Cook never looked back, organising trips further afield. In 1851 his company took more than 150,000 people on trips to see the Great Exhibition in London and started arranging tours around Europe. As the world’s first travel agency, Thomas Cook & Son expanded people’s horizons and gave the middle classes a new taste for travel as leisure.

The Wheels of Change

At around the same time, the very first pedal-powered velocipedes were emerging from the workshop of a Parisian coach-maker. Made from wood and iron, they were incredibly heavy; the punishing ride led them to become known as ‘boneshakers’. In 1868 James Starley’s sewing machine company in Coventry received an order from France to manufacture 400 of these new contraptions. The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war meant that the bikes were never delivered, but Starley had no trouble selling them on the domestic market. Sensing a business opportunity, he set about improving on the primitive French design.

New technologies like ball-bearings and wire-tension spokes led to the penny-farthings and tricycles of the first great bicycle boom in 1870s. These new machines demonstrated the true potential of human-powered locomotion, but high-wheelers were rather difficult and dangerous to ride, while tricycles were slow and cumbersome. In the 1880s Starley’s nephew, John Kemp Starley, came up with a new design that was a game-changer. The Rover ‘safety bicycle’ possessed all the essential characteristics of the modern bicycle as we know it today: two wheels of equal size, a diamond shaped frame, steering by a handlebar connected to the forks that held the front wheel, rear-wheel drive using a chain and variable sprockets. It was safe to ride, and gave people the speed and the comfort to travel considerable distances with a genuine sense of freedom and independence quite different from the regimented tourism of the Thomas Cook model. Even so, bicycles were still expensive objects to make. Only the relatively wealthy had the money and the time to indulge in this new and wildly popular pastime. Having perfected its form, the ingenious minds of the Midlands set about making the bicycle affordable to all. In the early 1900s, Coventry was shifting into making cars (Rover cars inherited the name from Rover bicycles) and the leading cycle manufacturers were based in Birmingham and Nottingham, though there were bicycle and component factories spread right across the region. The likes of BSA, Hercules and Raleigh vied for the crown of the world’s biggest bicycle manufacturer, and output rose year on year.

Meanwhile, another Midlands invention was opening up the countryside to these new self-propelled voyagers. In 1901, while out walking, Edgar Hooley, the chief surveyor for Nottinghamshire County Council, noticed an unusually smooth stretch of road near a Derbyshire ironworks. Locals told him that a barrel of tar had fallen from a cart onto the road, and someone had poured waste slag from the blast furnaces to cover up the mess. The result was a smooth and solid road surface with none of the ruts and dust that plagued the gravel road surfaces of the time. Hooley perfected the process of combining slag with heated tar, adding stones to the mixture to create a smooth and durable road surface. Radcliffe Road in Nottingham was the world’s first tarmac road; Hooley’s invention enabled cyclists of the inter-war years to explore further, in greater comfort and on ever lighter and faster machines.

Britain’s love affair with the bicycle reached its peak in the early 1950s. The country was producing 3.5 million bicycles a year. More than a quarter of British people cycled to work and more than a third of people living in rural areas used bicycles as their main mode of transport. For cycle tourists, Central England was a paradise, with its gentle countryside, labyrinth of lanes, pubs and tea-rooms in every town and village and a growing network of youth hostels for overnight stays. A typical day out was captured in the short film Cyclists’ Special in which groups of cyclists take a specially chartered train from London to Rugby for a day out riding in the heart of England. It is available to watch on YouTube and will have you yearning for the simpler times of steel bikes, leather saddles, stylish attire, no helmets and barely any cars on the roads.

It was in this golden era of cycling that a teenage girl growing up in wartime Coventry joined friends, who shared her taste for adventure, riding out of the bombed-out city centre to explore the Warwickshire countryside. After Eileen Sheridan had completed the classic ‘140 miles in 12 hours’ cycle-touring challenge, she started entering races, and was soon winning them. Though just 4 feet 11 inches tall she set national new records in time trials from 30 miles all the way up to 12 hours. Dubbed “the mighty atom”, Sheridan signed a lucrative professional contract with Hercules of Birmingham and broke every place-to-place record on the books. By the end of her 1954 Land’s End to John O’Groats record ride of 2 days, 11 hours and 7 minutes she was so cold and exhausted she was hallucinating phantoms and polar bears by the roadside and had to be spoon-fed. Her record was unbroken for 36 years. I have had the honour of meeting Eileen and she remains an inspiration as a remarkable athlete and as one of the great trailblazing women in sport. Her record-breaking bike is on display in the Coventry Transport Museum.

Shires, mires, spires and squires

Topographically, Central England is a shallow bowl with higher ground on three of its four sides. To the north are the Peak District and the Staffordshire Moorlands, to the south the Cotswolds and the Northamptonshire Escarpment. To the west are hills that rise towards the Welsh border, but to the east is the North Sea coast. Into this bowl flow Britain’s longest and third-longest rivers: the Severn from the hills of Mid-Wales, and the Trent from the Staffordshire moorlands. Their watersheds are separated by the slight dome on which stand Birmingham and the Black Country.

Both the Severn and the Trent have shaped the landscape through which they flow. The Severn once flowed north towards the Mersey, but during the last Ice Age it was blocked by an advancing northern glacier. The water built up into a lake that now forms the flat lands of Shropshire and the Cheshire Plain. The lake eventually overflowed southwards, creating the Ironbridge Gorge and a new course for the Severn via the Bristol Channel. The Trent once flowed due east across Lincolnshire into the North Sea but it was also blocked by a mass of ice that lay on what is now the Vale of Belvoir. The water was forced into another giant lake which emptied into the Humber Estuary.

Many of the region’s most important medieval cities and towns grew up at strategic crossing points along these two rivers and their tributaries. Shrewsbury, Worcester, Tewkesbury and Gloucester are all on the banks of the Severn, while Stoke, Burton, Nottingham and Newark are on the Trent. Even today there are several long stretches of river without a crossing point, which creates challenges for route-planning. Both rivers remain shape-shifters, meandering extravagantly across their flood plains and regularly bursting their banks after heavy rain. Central England’s network of rivers and man-made canals turbocharged the early phase of the industrial revolution until they were largely superseded by steam-powered railways.

The legacy of these transport networks today is more miles of rideable canal towpaths and rails-to-trails routes than in any other part of Britain. The most spectacular of these are in the southern half of the Peak District. Its canals and disused railways overlay a dense network of old roads, green lanes and packhorse trails. No area of Britain combines such a high density of routes for exploring by bike with such stunning landscapes, from windswept moors of purple heather and vertiginous gritstone edges to limestone crags and caverns. On its dales and upland plateaus, a vast patchwork of small fields includes a staggering 5,440 miles of dry-stone walls. Within easy reach of so many industrial towns and cities, it’s no wonder that the Peak District was the focal point for campaigns for greater land access and the right to roam. Those battles, including dramatic physical confrontations between ramblers and gamekeepers, led to the creation of Britain’s first national park. Today, some 20 million people live within an hour’s journey of the Peak District. Its tourist honeypots sometimes heave with visitors, but with a bicycle it’s still easy to find peace and solitude within a few minutes’ ride.

The Shropshire Hills are the region’s other big expanse of upland and open country. Some of the oldest and most unusual geology in England makes the area a mecca for rock hounds and cyclists with a taste for climbing. Shropshire has five peaks over 500m high. The county tops of Herefordshire and Worcestershire are both over 400m. Elsewhere, isolated local prominences like Cleeve Hill and May Hill in Gloucestershire, Ebrington Hill and the Burton Dassett Hills in Warwickshire, Bredon Hill in Worcestershire and the Wrekin in Shropshire all have views much bigger than their altitudes would lead you to think. And most have a road or a rideable track that will take you to the very top.

But there’s no hiding the fact that Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire are among the flattest counties in England. As if to rub it in, the highest point is the man-made spoil heap of the former Silverhill colliery which rises to 205m. Much of Lincolnshire is barely above sea level, though the crest of the Wolds feels higher and hillier than its greatest elevation of 168m. The Lincolnshire coast is one vast expanse of dune-backed mud flats and wind farms. There is a string of broad sandy beaches, including traditional bucket-and-spade resorts like Skegness and Cleethorpes, protected nature reserves and off-limits military firing ranges. Inland, Central England’s largest county is a bracing, big-sky landscape of marsh, fen and wold. As a landscape it could not be further removed from the intricate labyrinth of hills, lush valleys, small fields and wooded dells in Shropshire, Herefordshire and the areas of Worcestershire and Gloucestershire west of the River Severn.

East of the Severn, in Gloucestershire and southern Warwickshire is the geological feature that marks the boundary between Central and Southern England. It gives rise to one of the most celebrated English landscapes. The Cotswolds are a part of the broad and intermittent outcrop of limestone that extends from Lyme Bay in Dorset to the Cleveland Hills in North Yorkshire. The escarpment rises almost imperceptibly from the south-east to form a broad plateau with steep-sided valleys and a dramatic crest overlooking the Severn and the Vale of Evesham. The honey-toned limestone dates from the Jurassic period, when dinosaurs ruled the Earth and the first birds were just taking to the skies. It is the fossilised remains of a shallow tropical sea that once teemed with aquatic life.

Though largely arable today, the core of the Cotswolds was once home to vast flocks of sheep. Wool was the oil that fuelled the economy of medieval England. The wealth generated is still on show in the fine houses of wool merchants and the extravagant architecture of the richly-endowed ‘wool churches’. North-east of the Cotswolds, the hills are gentler and the soils more fertile. The combination of high-quality agricultural land, abundant building stone, good transport connections and plenty of open space to hunt wild animals are the reasons why this swathe of Northamptonshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire have so many large landed estates. The immense wealth derived from large landholdings, sometimes enriched by the spoils of colonialism and slavery, is expressed in grand country houses set in elegant landscaped parkland.

Dotted across Central England are some of the landscapes that have inspired some of England’s greatest literature. Although Shakespeare wrote primarily for a London audience, he divided his time between the city and his home town of Stratford-upon-Avon. His plays are dotted with places, people and events from the Warwickshire countryside. His duality as a man equally at home in the fields and villages of rural England and the metropolis of Elizabethan London adds richness and depth to Shakespeare’s genius as poet, dramatist and observer of the human condition.

D. H. Lawrence, the first great English novelist with truly working class roots, was a cyclist himself, if largely by economic necessity, though a short passage in Sons and Lovers captures the reckless thrill of riding at speed and, characteristically, his thoughts on its sexual significance. For Lawrence, the rural hinterland of the Nottinghamshire coalfield was “the country of my heart”. He delighted in the details of Eastwood and its environs and felt its deeper resonances, once writing that “the mines were, in a sense, an accident in the landscape, and Robin Hood and his merry men were not very far away”. George Eliot was born and raised in Nuneaton and she set Middlemarch, her greatest novel (for some, the greatest of all English novels), in a fictitious Midlands town. In The Mill on the Floss, the River Trent brings the story to its tragic climax. Lord of the Rings author J. R. R. Tolkien — who grew up in and around Birmingham and its suburbs — described The Shire, the idyllic homeland of the Hobbits, as “more or less a Warwickshire village” of the 1890s.

In certain respects, England’s overbearing North-South divide has left Central England as the squeezed middle. Midlanders’ typical reticence when it comes to blowing their own trumpets is an admirable trait, but it hasn’t exactly helped the region hold its ground against the economic and political might of the South-East and the powerful regional identity of the North. The cultures of the Midlands are so diverse that they elude simple categorisation. As Alan Sillitoe’s fictional creation, Arthur Seaton, who worked tedious shifts in the Raleigh bicycle factory in Nottingham, famously declared, “I’m me and nobody else; and whatever people think I am or say I am, that’s what I’m not, because they don’t know a bloody thing about me.” The hedonistic anti-hero of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is part of Nottinghamshire’s rebel tradition, from Robin Hood to the strike-defying coal miners of the 1980s and the stark beats and abrasive rants of Sleaford Mods. By most accounts, Birmingham and the Black Country is the birthplace of heavy metal, producing Black Sabbath, Judas Priest and half the members of Led Zeppelin. Worlds apart musically, but no less rebellious and just as deeply rooted in the West Midlands, was Coventry’s multi-racial, 2-Tone scene that included The Specials, The Selecter and The Beat, and Birmingham pop-reggae superstars UB40.

The Chinese word for China, Zhōngguó (中國), literally means ‘the country — or kingdom — in the middle’. Similarly, most of the great civilisations in and around the Mediterranean thought of this as the ‘middle sea’. There is pride and prestige in being at the heart of things. From the deep gorges of the Wye Valley to the heights of Lincolnshire Wolds, from small but perfectly formed Rutland to the magnificent wildness of the Shropshire hills, from the charm of the Cotswolds to the crags and cliffs of the Peak District, and everywhere that lies in between, Central England is a vast and varied territory to explore. You can’t miss it. It’s bang in the middle.